Friends of Vocational Technical & Agricultural Education,

In the event you did not wee this piece earlier this month, we are sharing it with you.

As we move away from MCAS as the standard for high school graduation, we need to ensure that Chapter 74 vocational technical & agricultural programs are given sufficient importance and weight since they are teaching integrated academic competencies like other academic courses.

Erika Giampietro, executive director for the Massachusetts Alliance for Early College, said she hopes whatever path the state takes next focuses on the “competencies” students graduate with, especially those that truly matter in the real world.

“[Employers] are not saying, ‘I wish kids had taken two years of foreign language, four years of English and four years of math.’ They’re saying, ‘Yeah, kids aren’t coming with strong enough executive functioning and clear enough communication skills and showing up to work every day and realizing how important that is to be on time,‘” Giampietro said.

David

With no more MCAS requirement, graduation standards vary widely among state’s largest districts

Will state leaders take action to address disparities post-Question 2?

By Mandy McLaren Globe Staff

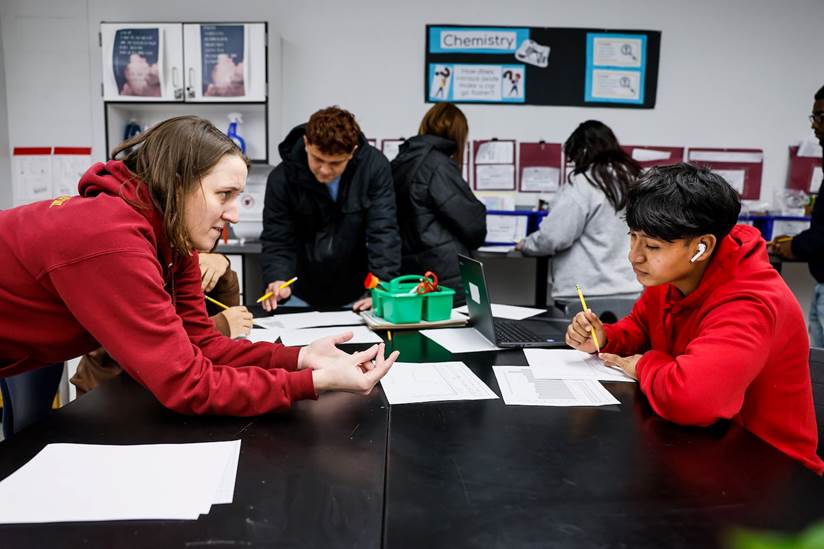

Science teacher Jamie Kendall provided one-on-one guidance to Gender, 17, during class at Chelsea Opportunity Academy. Chelsea Public Schools requires all high school students to take a rigorous course load, including lab-based science classes, in order to graduate.

What’s a Massachusetts high school diploma worth? These days, it depends.

There used to be a standard measure: passing scores on the 10th-grade math, science, and English Language Arts MCAS exams.

But now that voters have struck down the state’s longstanding requirement for students to pass those exams in order to graduate, the answer is more complicated.

A Globe analysis of the largest 50 districts’ high school graduation requirements found a wide variation among math, science, and foreign language requirements — a range advocates say creates inequitable opportunities for students.

The Globe’s analysis comes as education officials and lawmakers weigh whether to take action to address the lack of uniformity.

What changes now that Question 2 passed?

Effective beginning with the class of 2025, students no longer need to pass the 10th-grade MCAS to graduate. They do, however, have to meet local graduation requirements, which are set by the state’s more than 300 school committees.

The Globe’s analysis found nearly all of the large districts require four years of English and three years of social studies. But while some explicitly require rigorous math and science courses, many others don’t. Foreign language requirements are uneven, too, with 31 of the 50 districts mandating the courses.

There is no obvious trend in the requirements, with both high- and low-income districts maintaining different standards.

The variation means students may leave high school with the same Massachusetts diploma but with vastly different educational experiences. To be sure, this was true before voters approved Question 2. But whereas, in the past, MCAS was used as a measure to ensure similar qualifications, that uniform performance bar no longer exists.

The risk moving forward, said Andrea Wolfe, president and CEO of MassInsight, a Boston-based education nonprofit, is that a Massachusetts diploma could become “meaningless.”

“It is not that seal, that promise that we gave to students and families that they will be successful in whatever their choice is after high school,” Wolfe said.

Erin Cooley, Massachusetts managing director for Democrats for Education Reform, a group that advocated against Question 2, agreed.

“We’re basically saying that a diploma from Weston is different than a diploma from Lawrence is different than a diploma from Haverhill,” she said.

How do high school graduation requirements differ?

A Globe review of high school graduation requirements found a dozen of the state’s 50 largest districts require all students to take and pass coursework that would make them eligible for admission to the state’s flagship public university, UMass Amherst (as well as all of the state’s public colleges and universities).

Those districts — which include Attleboro, Braintree, Chelsea, and Lexington — require students to take four years of English; four years of math, including at least Algebra 2; three years of lab-based science; at least two years of social studies, including US History; and two years of the same foreign language.

Attleboro Public Schools Superintendent David Sawyer said he was surprised other districts don’t require the same coursework, which, he said, holds students to high expectations — “one of the most important ingredients to student success.”

The high standards in the district’s coursework came about roughly 15 years ago, in part, because of MCAS, Sawyer said.

“I would be the first person to say that MCAS is a flawed measure, but the high expectations that it installed is really the sort of secret sauce,” he said.

Chelsea Public Schools Superintendent Almudena Abeyta also said rigorous preparation is instrumental, especially for her many students who will be the first generation in their families to attend college.

“We work so hard to get them into college, we don’t want them to fail when they get there,” Abeyta said.

<![if !vml]> <![endif]>Staff member Kathryn Roldan provided one-on-one guidance to Alexis, 20, during class at Chelsea Opportunity Academy. Chelsea Public Schools requires high school students to take a rigorous course load, including lab-based science classes, in order to graduate.

<![endif]>Staff member Kathryn Roldan provided one-on-one guidance to Alexis, 20, during class at Chelsea Opportunity Academy. Chelsea Public Schools requires high school students to take a rigorous course load, including lab-based science classes, in order to graduate.

Should school districts require MassCore?

Other districts, such as Newton, said while they do not currently maintain the state university requirements, most of their students voluntarily take a rigorous course load through MassCore.

MassCore is a state-recommended sequence of courses for students to take to be prepared for college and beyond. A report earlier this year, however, found half of all high schools in the state don’t require students to follow it.

State Senator Jason Lewis announced in September that he would file legislation mandating districts follow MassCore if Question 2 passed (the new session starts in January).

“Requiring completion of MassCore in order to receive a high school diploma would strengthen course offerings across all high schools, ensure that all students are receiving a rigorous education, and provide a consistent statewide graduation standard,” Lewis said at the time.

But not everyone is sure MassCore, which was last updated in 2018, is the right solution. In particular, requiring MassCore without providing additional funding would not address current inequities, advocates told the Globe. Some schools, for example, don’t require three years of lab-based science because they don’t have enough classroom lab space to do so, Cooley said.

“If we make some sort of state change and require courses as part of our state graduation requirement, we really have a lot of work to do to make sure that’s equitable across our districts,” she said.

What might the state do now?

Asked about its stance on MassCore, Max Page, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, which funneled more than $15 million into supporting the passage of Question 2, said the union hasn’t yet finalized its agenda for the next legislative session.

The union does, though, want to see the creation of a “blue ribbon commission” to study alternative graduation requirements, Page said. “We stopped what we think was really harmful, and we’ve opened up the new discussion,” he said.

Erika Giampietro, executive director for the Massachusetts Alliance for Early College, said she hopes whatever path the state takes next focuses on the “competencies” students graduate with, especially those that truly matter in the real world.

“[Employers] are not saying, ‘I wish kids had taken two years of foreign language, four years of English and four years of math.’ They’re saying, ‘Yeah, kids aren’t coming with strong enough executive functioning and clear enough communication skills and showing up to work every day and realizing how important that is to be on time,‘” Giampietro said.

Giampietro and others said they see this moment as an opportunity for Massachusetts to be innovative, especially in light of other states’ extensive requirements. “Everybody else is ahead, more stringent, more rigorous,” Giampietro said. “For Massachusetts, who has a lot of pride in being first in having quality education, I think we want to continue to say that’s true for us.”

Russell Johnston, acting commissioner of the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, said in a statement that the department “remains concerned about disparities in curriculum and graduation requirements.”

“These decisions are made locally but DESE is committed to assisting school districts provide students with an excellent education experience,” he said.

David J. Ferreira

MAVA Communications Coordinator

DavidFerreira